Ian Boisvert was a 2011 Ian Axford Fellow in Public Policy through Fulbright New Zealand. Ian is now returned to San Francisco, California, where he practices renewable energy and environmental law.

Part One: Introducing the Mountains of “Blue Tape”

New Zealand and the United States share many characteristics. They each have Anglo-derived common law systems, English is the lingua franca, and both support liberalized, capital markets. For all these commonalities and more, they could not have more dissimilar regulatory regimes for permitting offshore renewable devices such as wave energy converters, tidal turbines and wind turbines.

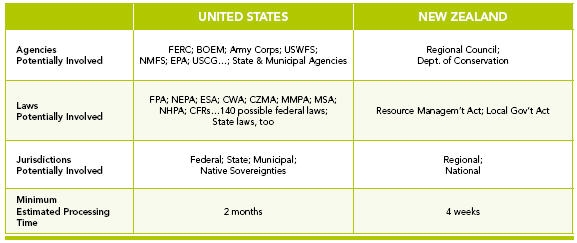

To put a device in the ocean without being connected to the grid a developer in the United States may have to deal with three different governments (federal, state, and native sovereignty) each with multiple agencies who enforce a dizzying web of laws and regulations on different timeframes. A developer in New Zealand, on the other hand, has to deal with one central government, one authorizing body at the local level, and, for the most part, one statute.

The difference in the amount of “blue tape” standing between the developer in United States and the one in New Zealand can be measured in years and millions of dollars. And that is just for pilot project development. When a proposed development increases to a commercial scale that difference dissipates: both the New Zealand and United States developer faces the possibility of spending millions of dollars over years just to obtain permission to build. Still, for all the well intentioned policies and Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) that United States agencies and states create to make pilot permitting more streamlined, the United States developer faces a longer, harder, more complex process than its New Zealand equivalent.

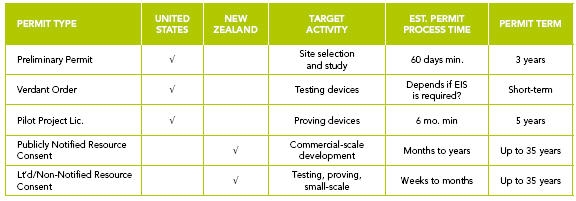

Part Two of this article explains the three United States permits suited to deploying pilot-scale ocean renewable devices. Part Three explains the New Zealand consent process for a similarly scaled project and contrasts that with the United States approach. Part Four examines, with two brief case studies, why neither the United States’ nor New Zealand’s permitting processes are equipped to handle commercial scale ocean renewable development. Part Five concludes with lessons for regulators in both countries.

Part Two: United States’s Mountain Chains of Blue Tape

Ocean renewable power developers in the United States intent on deploying a pilot scale device must deal with federal and state agencies and laws. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is arguably the most important of the federal agencies because under the Federal Power Act it has authority to regulate and license hydroelectric projects on navigable waters.26 A developer must get FERC approval to operate the device, whether a pilot project will lie within an adjoining state’s jurisdiction of three nautical miles from shore (ten miles for Texas and parts of Florida) or back into federal jurisdiction beyond the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

Over the decade since FERC first asserted jurisdiction over an ocean energy project in Makah Bay, Washington, three types of permits have emerged for pilot-scale projects.27

The three types are: preliminary permits, “Verdant Orders”, and pilot project license policy.

A preliminary permit allows a potential developer to explore and investigate a site for up to three years.28 The applicant applies through submitting a plan to conduct baseline studies for the preferred site.29 Inreaction to public comments FERC now reviews these applications on a “strict scrutiny” basis to avoid potential “site banking.”30 FERC will take at minimum 60 days to process the application, but that could extend to years under certain conditions.31 That is, whether the myriad other federal, state, or tribal agencies intervene.

The value of the preliminary permit for the prospective developer is to secure a site, study the site’s viability for the proposed device(s), and to engage the site’s other stakeholders in voluntary, early consultation. The obvious drawback is that the developer may not deploy or operate any device in the site with only the preliminary permit. If the developer is prepared to move beyond mere site investigation and has an experimental device it would like to test, the Verdant Order is the appropriate permit to apply for. A Verdant Order arose from a FERC interpretation of the Federal Power Act as it applied to Verdant Power LLC’s efforts to site its experimental tidal turbines in New York’s East River.32 To secure a Verdant Order the applicant must be seeking to conduct studies on an experimental technology only for a short time (undefined) and, critical to a successful application, any power generated does not displace and is not trasmitted to the national grid.33

Importantly, under a Verdant Order the applicant-developer might still have to obtain all other necessary approvals such as the Clean Water Act Section 404 and 401 permits, Endangered Species Act Section 7 permit, as well as state, municipal, and, where applicable, tribal approvals.34

The value of the Verdant Order permit is that it allows the developer to avoid full-blown FERC commercial license procedures, which can be quite daunting, to test a few experimental devices for a short period of time. However, one drawback is the developer may still have to adhere to multiple other environmental permits that could, as in the case of Verdant, lead to years of permit hearings and studies. The other drawback is that the developer can only test the device for its operation in the water and not truly its ability to generate electricity because of the limitation against displacing power in the national grid.

If a device developer is interested in both testing pilot-scale devices and generating electricity that enters the grid then FERC’s pilot project license is the relevant permit. The pilot project license is only a policy that flows from FERC’s interpretation of 18 CFR 5.18.35 Because it is not law, FERC is not legally bound to follow it. The requirements for an application to be considered for the pilot project license are

(1) small scale (e.g., 5 MW or less);

(2) must avoid “potentially” sensitive areas as described by the applicant,commented on by stakeholders, and determined by FERC;

(3) devices can be shut down or removed on “short notice” if “unacceptable risks” arise—FERC defines neither term more explicitly;

(4) applicant must seek either a multi-decade license or completely decommission site at end of pilot project license duration; and

(5) the applicant initiates the permit through a draft application that offers sufficient information for environmental analysis.36

The last point means the applicant must still get all other environmental approvals from other federal, state, and, where applicable, tribal agencies. These include Army Corps of Engineers issued Clean Water Act Section 404 and 401 permits, National Marine Fisheries Service approvals for devices in “Essential Fish Habitat,” as well as National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Mammal Protection Act approvals. If an applicant succeeds in securing all necessary approvals, the pilot project license permits the developer to test its technology and transmit electricity into the national power grid, as well as pursue a standard license application following the pilot project license.37 However, an application for a standard license must be initiated 5 years prior to generation. Paradoxically, the applicant must simultaneously apply for the pilot project license and standard license even though the applicant will not have yet collected the data to support the standard license.

Moreover, a wide array of stakeholders can comment on and make recommendations about the applicant’s proposed plans, overall draft application and request for waivers, which further complicates and adds time to the application process. Even after FERC accepts the application, parties can still file interventions and comment on the application and monitoring and safeguard plan proposals. Any of these delays in processing time eats into the five-year timeframe for which the applicant has to test its devices.

The value of the pilot project license is, according to FERC, a streamlined permit process offering device developers an opportunity to test devices, collect in situ data, and build the case for commercial development. The drawbacks, though, are significant. The application approval process is likely to take over 12 months because of the additional authorizations and opportunity for public comment and intervention. That delay reduces possible operations within the 5 years the pilot project license runs.

Moreover, if a developer wanted to pursue a commercial-length FERC lease, the pilot project license would be of little value, because the developer would need five years to complete the commercial lease process. The developer will not have that data until after the pilot project license ends. Consequently, no ocean renewable developer in the United States has secured a pilot project license in the three years since FERC made it available.

Comparing United States and New Zealand Regulatory Regimes

Part Three: New Zealand’s Hills of Blue Tape

New Zealand ocean renewable developers face a wholly different consenting regime than their United States counterparts. The New Zealand regime is governed by the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), which is the prevailing statute for any project that uses natural resources. Its overarching purpose is to guide “sustainable development” through an “effects-based” testing model that addresses the extent to which a proposed project affects the environment.38

The RMA’s relevance to prospective ocean renewable energy developers is that it lays out the consent process by which regional government bodies approve developments. The RMA offers three tracks the developer can pursue:

(1) limited- or non-notification;

(2) public notification; and

(3) call-in process.

For a pilot or small-scale project, the most relevant and useful track is the limited/non-notified consent process. Although developers can request a particular track, regional government bodies ultimately make that decision.

Part 6 of the RMA lays out the process for securing resource consents. One of the first steps is that the consent authority determines whether the applied-for project should be publically notified or not. If the authority determines the proposal only needs limited notification then the consent authority must decide if there are any affected persons, customary rights group or customary marine title group in relation to the activity.39 Under the RMA an “affected person” must have some nexus with a project such that the “activity’s adverse effects on the person are minor or more than minor (but are not less than minor)” and determination made by consent authority.40 Whether “adverse effects [are] likely to be more than minor” is determined by the consent authority.41 However, a project applicant can limit the number of “affected persons” by getting written pre approval from persons to undertake the proposed project.42

For limited- or non-notification consultation requirements only those people served with notification of the application have the right to make a submission (comment) on the application.43 Moreover, they must also prove their submission shows they are likely to be directly affected by an adverse effect that the proposed project will have on environment.44

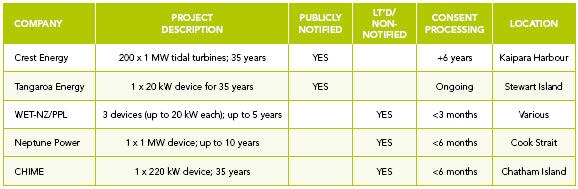

The value of proceeding with a non- or limited-notification resource consent hearing means the scope of input the developer needs to actively solicit, and therefore respond to, is much less than with a public notification hearing. Consequently, the developer can expect a relatively rapid hearing process as compared to if the developer were pursuing a US permit for a similarly scaled project. A regional council would be very unlikely to accept a non- or limited-notification resource consent for a large- or commercial-scale project. For example, Crest Energy Ltd. sought to deploy 200 x 1 MW tidal turbines in the narrow mouth of the Kaipara Harbour and had to follow a public notification process, which took over 6 years. In comparison, Chatham Islands Marine Energy Ltd. secured a non-notified resource consent in under 6 months for a single 220 kW oscillating water column device to be installed near Point Durham, Chatham Island, for up to 35 years.

In short, limited notification gives an applicant a much higher chance of gaining approval within a few months and reduces the chance of litigation. It is thus like FERC’s Pilot Project Policy License without the regulatory and concomitant temporal uncertainty.

New Zealand Limited/Non-Notification Vs. Public Notification

Part Four: Commercial Scaling - The Impassible Mountain of Blue Tape

The New Zealand and United States governments proclaim supporting innovative, clean technology that mitigates climate change and promotes job creation. But marine renewable device innovators and project developers are experiencing respective regulatory regimes, which are not in synch with that broader message. As noted above, Crest Energy proposed a 200 tidal turbine array in 2006. Because of the scale of their project, Crest Energy had to follow the public notification process. Over the next 5 years the company faced public opposition, opposition from the Department of Conservation, and risk aversion from there source consent authority, the Northland Regional Council, who was uncertain of what environmental effects the development might have. Accordingly, the first commercial-scale marine renewable project in New Zealand has so far cost Crest Energy hundreds of thousands of dollars and upwards of 5 years just to secure consent to develop. After Crest Energy achieved final consent approval, the conditions Northland Regional Council imposed on their development add further doubt as to whether Crest Energy will be able to fully develop their project before 2022.

In the United States, Energy Management Inc. (EMI) has been entangled in a similar experience over the development of Cape Wind. In the early 2000s EMI proposed an offshore wind farm of 130 wind turbine off the Massachusetts coast. The regulatory landscape alone has been daunting: seventeen Federal and State agencies are involved with overlapping jurisdictions, inconsistent timelines, and each enforcing numerous and different statutes and regulations. Additionally, EMI has had to face opposition - allowed because ofthe notion of “public attorneys general” written into many environmental laws - from local landowners, Indian Tribes, fishing interests, and environmental groups. The multi-dimensional scale of the regulatory hurdles makes commercial-scale marine renewable energy development in the United States a lawyer’s dream but a developer’s nightmare.

Part Five: A Suggestion to Regulators: Scale Back the Blue Tape

New Zealand and the United States have both nationally proclaimed interest in promoting marine renewable energy development. Nonetheless, developers in both countries have faced, and continue to face, complex regulatory frameworks with multi-year timeframes for commercial-scale development. As such, it appears both countries have room to make meaningful changes to their regulatory regimes that could reduce a major obstacle to marine renewable energy development. Part of the change could be a shift in what appears to be institutional risk aversion, which marine renewable energy developers face, due to bureaucratic unfamiliarity with marine energy projects and their environmental effects. Whereas offshore oil development in the United States can secure permits in less than one year, marine renewable developers experience much longer timeframes although the greatest risk renewable development represents pales in comparison to that of offshore oil drilling platforms. In light of this, regulators could consider reducing institutional risk aversion to marine renewable energy development, streamline and coordinate their permit requirements and process schedules, and align regulatory regimes with national proclamations of support by designing one-stop permitprocesss for commercial-scale marine renewable energy development. Without reducing the amount of “blue tape,” marine renewable energy developers may have a difficult time scaling their pilot projects tocommercial scale developments.

26 16 USC sec. 817(1).

27 Prof. Rachael Salcido, Siting Offshore Hydrokinetic Energy Projects: A Comparative Look at Wave Energy Regulation in the Pacific Northwest, 5 Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal 109, at 125 (2011).

28 16 USC sec. 797(f).

29 18 CFR 4.81

30 Prof. Rachael Salcido, Siting Offshore Hydrokinetic Energy Projects: A Comparative Look at Wave Energy Regulation in the Pacific

Northwest, 5 Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal at 131 (2011).

31 Pacific Energy Ventures, Siting Methodologies for Hydrokinetics: Navigating the Regulatory Framework, p. 14 (December 2009).

32 Verdant Power, LLC, 111 FERC 61,024 (2005), on reh’g, 112 FERC 61,143 (2005).

33 Pacific Energy Ventures, Siting Methodologies for Hydrokinetics: Navigating the Regulatory Framework, p. 14 (December 2009).

34 Stoel Rives LLP, The Law Of Marine And Hydrokinetic Energy, ch. 3, at 4 (4th ed. 2011).

35 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Licensing Hydrokinetic Pilot Projects White Paper (Apr. 14, 2008), available at

www.ferc.gov/industries/hydropower/indusact/hydrokinetics/pdf/white_paper.pdf

36 Id.

37 Id.

38 Resource Management Act (1991), Section 5, Paragraph 1.

39 Resource Management Act (1991), Section 95E-F.

40 Resource Management Act (1991), Section 95E(1).

41 Resource Management Act (1991), Section 95D.

42 Resource Management Act (1991), Section 95E(3).

43 Resource Management Act (1991), Secs. 95(B) & 96(3).

44 Resource Management Act (1991), Sec. 308B.